AI-driven technologies for human wellbeing

Published: 03.11.2025 / Blog / Publication

In mental health, AI tools provide timely support and bridge gaps in traditional care. This blog post explores the intersection of AI-enhanced user experience and its implications for mental health support, by reporting from a Blended Intensive Program (BIP) in Estonia, where prototypes were developed by international students for a local startup company.

Background

According to WHO (World Health Organization, 2022; 2025) mental wellbeing is not merely the absence of illness — it is a vital pillar of both personal health and collective societal resilience, shaping how we think, feel, connect, and thrive. Mental health challenges affect over 13% of the global population — with nearly 970 million people living with mental disorders in 2019. Women account for 52.4% of this group, while men represent 47.6%, reflecting the urgent need to address mental wellbeing through a gender-sensitive lens (WHO, 2022) According to Elgendi and Menon (2019) anxiety disorders are leading mental health issues worldwide. WHO (2022) confirms that anxiety and depression dominate the global mental health landscape, with 301 million individuals living with anxiety disorders, making up 31% of all mental illnesses, and 280 million affected by depressive disorders.

With technology developing at a rapid pace, it is important to understand the mental wellbeing of an individual and how artificial intelligence (AI) can be used in the treatment of depression and anxiety. For example, in a study by Baghaei et al. (2021), the approach called virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) was identified in the treatment of anxiety or depression in the clinical environment. In another study, Hickey et al. (2021) focused on wearable devices that are part of our daily lives and how these can help detect, for example, anxiety.

AI-driven wellbeing solutions have attracted sustained interest among researchers over the past years. Mental health support tools have consequently become more widely accessible, and we have seen portable, compact, and precise devices develop (Weenk et al., 2020; Peake et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2017). Elgendi and Menon (2019) highlight the usability of wearable devices regardless of time or location. Hickey et al. (2021) emphasise the value of technologies that enable early detection or effective symptom management, noting the urgent need for further research into anxiety and depression to help mitigate the global burden of mental health issues. Given that mental health technologies cross-over multiple academic disciplines, AI-driven solutions and user experience have been explored from various perspectives (e.g., Scott & Kercher, 2024; Baghaei et al., 2021; Maples-Keller et al., 2017; Anderson et al., 2016). Many of these studies report promising outcomes and propose directions for future research. WHO (2025), in their report, mentions that we need to, in general, scale up and diversify the help for anxiety and depression, and mentions that, for example, forms of self-help can become valuable.

Therefore, this blog post explores the intersection of AI-enhanced user experience and its implications for mental health support, by reporting from a Blended Intensive Program (BIP) in Estonia, where prototypes were developed by international students for a local startup company.

The aim of the BIP

The aim of the BIP was to solve a concrete client problem related to AI-driven tools and user experience. The BIP took place at TTK University of Applied Science in Estonia 31.3-4.4.2025 and brought together 24 students from Finland, Germany, Estonia, and Latvia. Participating universities included Arcada University of Applied Sciences (Finland), Hochschule Harz (Germany), Kaunas University of Technology (Lithuania), and TTK (Estonia). The client in this case was Mental Pin (https://www.mentalpin.com ), an Estonian company. Student teams (5 teams with 4-5 students per team) were to come up with ways of deploying and possibly also develop the product of the company. To be more specific, the teams were to innovate around a concept called “Companion for Calm” for the Estonian startup Mental Pin.

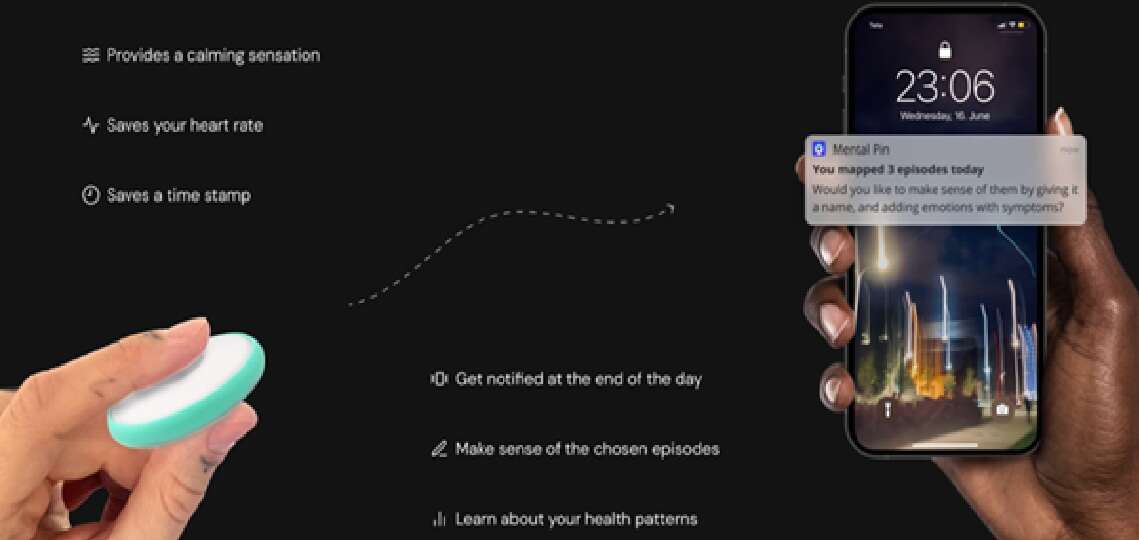

Mental Pin is developing a compact, discreet tool that aims at supporting women in managing anxiety. This pocket-sized device (see Fig.1) helps users centre their attention on their heartbeat, encouraging mindfulness and grounding during stressful moments. By redirecting focus from overwhelming emotions to physical sensations, it provides immediate relief a sense of calm. Paired with a companion app, the device also records each session, allowing users to monitor their experiences and gain deeper insights into their anxiety patterns over time (Mental Pin, 2023; Petoffer, 2020).

Figure 1. Mental Pin device paired with a companion app, screenshot from website (https://www.mentalpin.com/ , accessed 26.5.2025).

The sprint method

The key platform for developing the concept was the BIP, which provided the framework for international teamwork and collaboration. To support this objective, the sprint methodology was used to guide the innovation work to be done for Mental Pin. The sprint process used in this BIP was based on Google sprint (Knapp, 2016) and the sprint version we used had been developed further by the VAKEN network (www.vaken.org ) (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Our sprint was guided by the process according to the model developed in VAKEN (see www.vaken.org ).

Using the sprint method, a fast-paced five-day innovation framework, students worked in diverse international teams to research, brainstorm, prototype, and test relevant digital and AI-driven solutions targeting mental wellbeing. The sprint emphasised hands-on learning, collaborative problem-solving, and human-centered design, empowering participants to co-create practical tools in response to growing mental health concerns. Our sprint consisted of the following steps:

- User Research: Conducting in-depth explorations into how individuals experience and document anxiety, gathering unique insights through interview with possible end users, observations, and case studies.

- Rapid Prototyping: Engaging in iterative cycles of building, testing, and refining prototypes to learn quickly and tangibly. This process allows students to experiment with AI integrations, user interfaces, and interaction models to find what resonates the most with users.

- Learning by Doing: By taking a hands-on approach to building prototypes, the students aim to uncover insights about user behavior, mental health journaling needs, and AI's potential to facilitate self-reflection and therapy.

Results from the sprint

The five teams created prototypes, blending AI, digital design, and sensory elements to support users dealing with anxiety.

The following prototypes were developed:

- Enhanced solution for the Mental Pin is an attachable version of the pin designed to connect directly to the mobile phone. The team also enhanced the ‘Mental Pin’ mobile app with new features, including sleep and menstrual trackers.

- Trinity calm is a wearable concept in the form of a detachable, three-layered necklace. A Wearable Wellness Companion, designed to support emotional wellbeing.

- The CalmRing is a product which comes with a ring and an app, and provides helpful information, breathing exercises during a panic attack and stores emergency contacts.

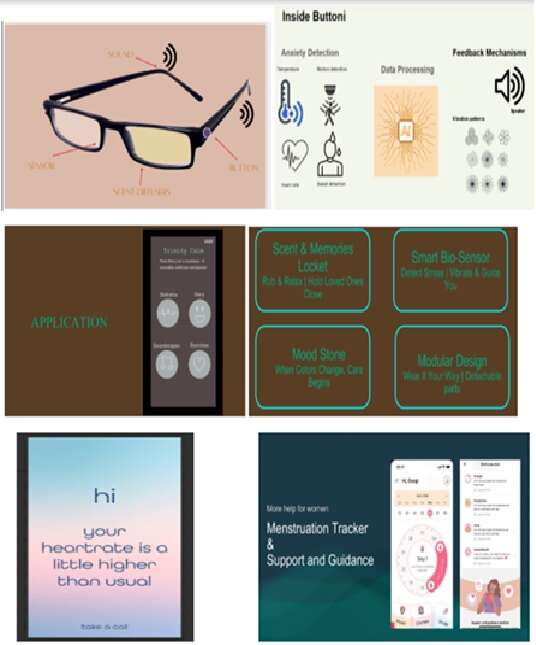

- Buttoni is a wearable device which listens, learns and calms. It is meant for anxiety detection and comes with a detachable patch.

- Calmor Glasses is a calming device in the form of glasses. Uses both scent and sound to enhance a sense of calm.

Figure 3 visualises the prototypes or features of the created prototypes.

Figure 3. Visualisations of the different prototypes, by the BIP teams

Note: Up to the left – Calmor Glasses, up to the right – Buttoni, middle left – Trinity calm wireframe, middle right – Trinity calm attributes, down left- Trinity calm mobile screen example, down right – enhanced solution for the Mental Pin.

Conclusions

As mental wellbeing becomes a growing global priority, especially among younger generations, programs like this BIP and the sprint method demonstrate how concrete ideas, concepts and prototypes can be developed for technology startups in the wellbeing and mental health sector. Our BIP ended with a presentation of the prototypes to the company Mental Pin. We received great feedback and look forward to hearing if our solutions are considered in the company's next step.

Contributors

Christa Tigerstedt (PhD), Principal Lecturer in Business

Sandradura Sachini, BA student International Business

Gimhani Shanilka Nisanjalee Kankanam Pathiranage, BA student International Business

Dinushi Ahangama Walawage, BA student International Business

Liisa von Schoultz, MA student Healthcare Leadership

Dushani Navindra Gunawardana Mudalige, BA student International Business

Mohsin Habib (PhD, MBA), MA student International Business Management

Rasheena Nalawangsa, BA student International Business

References

Anderson, P., Edwards, S. & Goodnight, J.R. (2016). Virtual reality and exposure group therapy for social anxiety disorder: results from a 4–6-year follow-up. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(2), 230-236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9820-y

Baghaei, N., Chitale, V., Hlasnik, A., Stemmet, L., Liang, H.N. & Porter, R. (2021). Virtual Reality for Supporting the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety: Scoping Review. JMIR Mental Health, 8(9), e29681. https://doi.org/10.2196/29681

Elgendi, M., & Menon, C. (2019). Assessing Anxiety Disorders Using Wearable Devices: Challenges and Future Directions. Brain sciences, 9(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9030050

Hickey, B. A., Chalmers, T., Newton, P., Lin, C.-T., Sibbritt, D., McLachlan, C. S., Clifton-Bligh, R., Morley, J., & Lal, S. (2021). Smart Devices and Wearable Technologies to Detect and Monitor Mental Health Conditions and Stress: A Systematic Review. Sensors, 21(10), 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21103461

Knapp, J. (2016). Sprint. London: Penguin Books.

Lin, A., Cheng, F., & Chen, C. (2017). Use of virtual reality games in people with depression and anxiety. University of Kentucky. https://www.cs.uky.edu/~cheng/PUBL/Paper_ICMIP2020.pdf

Maples-Keller, J. L., Bunnell, B. E., Kim, S. J., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2017). The Use of Virtual Reality Technology in the Treatment of Anxiety and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Harvard review of psychiatry, 25(3), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000138

Mental Pin. (2025). https://www.mentalpin.com/

Peake, J. M., Kerr, G., & Sullivan, J. P. (2018). A Critical Review of Consumer Wearables, Mobile Applications, and Equipment for Providing Biofeedback, Monitoring Stress, and Sleep in Physically Active Populations. Frontiers in physiology, 9, 743. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00743

Petoffer, M. (2020). Mental pin: Tangible assistant for tackling destructive compulsive acts and bringing one’s body out of the state of anxiety. MA Degree Project. Estonian Academy of Arts. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/ay8rz1t8w25igxow1wlqv/Mariin-Petoffer.pdf?rlkey=izzkpy3p8ktikuxw88rrsoahj&e=2&dl=0

Scott, Z. & Kercher, H. (2024). Partners in care: enhancing communication, minimizing provider burnout, and creating equitable care partnerships. Interaction Design, Faculty of Design, The Estonian Academy of Arts. https://eka.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_fd579755-ee61-4d48-8f37-8b5c03c4287f/

VAKEN (2024). The VAKEN handbook. https://www.vaken.org/

Weenk, M., Bredie, S. J., Koeneman, M., Hesselink, G., van Goor, H., & van de Belt, T. H. (2020). Continuous Monitoring of Vital Signs in the General Ward Using Wearable Devices: Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(6), e15471. https://doi.org/10.2196/15471

World Health Organization (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all.

World Health Organization (2025). Guidance on mental health policy and strategic action plans. ISBN 978-92-4-010679-6. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338