Are consumers using AI applications to search for information about products before making a purchase?

Published: 01.09.2025 / Publication / Blog

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being used to help consumers in various situations. In this blog post, we discuss the results of a survey on consumer use of various sources of information (including generative AI applications) to search for product information for different types of products.

Background

An important part of consumers' decision-making process when purchasing products is the availability and use of different types of information sources (Bettman et al., 1991; Haridasan et al., 2021). The search for product information at the pre-purchase stage has been examined from different perspectives and in different contexts (e.g. Akalamkam & Mitra, 2017; Broilo et al., 2016; Honka et al., 2024; Singh & Swait, 2017). On the other hand, consumers' information seeking behaviour is evolving as new types of information sources emerge, especially online and with the help of artificial intelligence (AI). According to Akalamkam & Mitra (2017), consumers tend to use both online and offline sources of information when shopping for goods. Typical online information sources are search engines (e.g. Google search), brand or retailer websites/mobile apps, price comparison sites and social media sites (e.g. Facebook, Instagram, TikTok).

Now, with the development of AI, the consumer can also obtain product information from chatbots and generative AI applications (e.g. ChatGPT) trained on the basis of large amounts of data. According to Pham et al. (2024), AI-powered search engines will revolutionise the information process, as AI will simply provide users with faster and more accurate searches. Therefore, it is interesting to study the (disruptive) potential of AI in consumer information retrieval and to see to what extent AI, as a relatively new technology for consumers, is used by consumers to search for product information within different product categories.

Product involvement

Based on prior research (e.g. Eriksson et al., 2018; Santos & Gonçalves, 2024), we should distinguish between how consumers seek information about different types of products. Different product features provide different types of customer involvement, and thus also different needs for information.

A product is typically considered a high-involvement product when a consumer has a lot to learn about its features and brand (Zaichkowsky, 1985). It is also typical of these types of products to be expensive, risky, rarely purchased, and/or have emotional value. Electronics and luxury products are products that usually induce deep involvement. The opposite is products with low engagement, where consumers engage very little with the product's features and brand. Low-involvement products typically include habitual consumer behaviour; consumers simply take only what they need off the shelf. Low prices are also often associated with products with low involvement. Consumers often perceive household items or groceries as low-involvement products, although they can also be engaging at times (Beharrell & Denison, 1995). Therefore, consumers are also likely to use different information sources and to a varying degree, depending on the type of products they intend to buy.

Survey

To get a better understanding of what types of information sources consumers use for different product categories and how high AI-based information sources rank, we have analysed survey data (N=2536) from a national consumer survey conducted by the Finnish Retail Research Foundation, University of Jyväskylä and the market research company Norstat (Data: Finnish Retail Research Foundation, 2024). In the survey, respondents were divided into responding to a product group from which they had purchased a product in the past year. The survey program ensured that there was an even distribution of responses by product group. See figure 1 for the ten product groups.

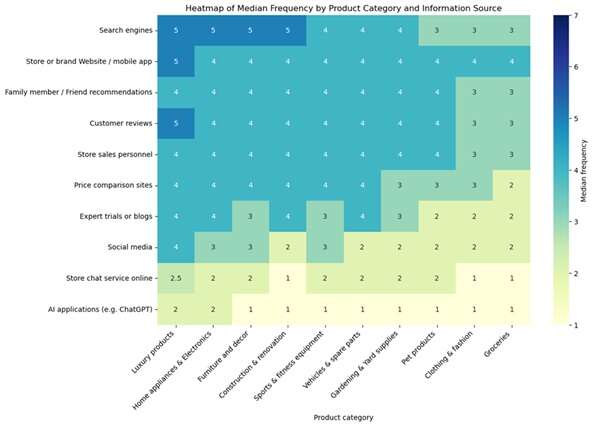

The heatmap in Figure 1 compares the different product groups and the sources of information used for each. Groceries are ranked lowest and luxury products highest based on median usage frequency for the ten different information sources investigated. We also conducted a statistical non-parametric test and concluded that there are significant differences between the categories, especially between groceries and the top-rated categories (Luxury products, Home appliances & electronics).

Figure 1. Heat map of median frequency by product category and information source (generated with the help of MS Copilot).

Note: Question: How often do you use the following sources of information when searching for product information or comparing options? Scale: 1, Never – 7, Almost always. The product categories are ranked from left (highest) to right (lowest) based on median usage frequency of all information sources. Similarly, information sources are ranked from top (highest) to bottom (lowest).

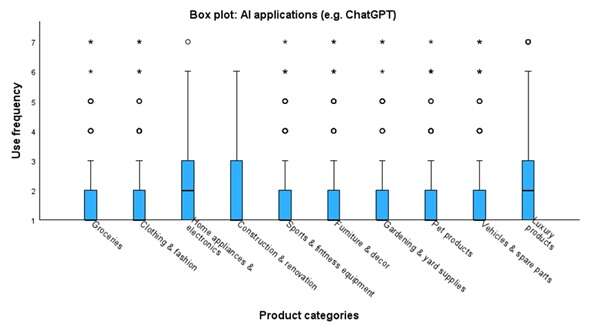

AI applications along with online chat services rank low across all product categories included, suggesting low usage overall for these types of applications. Search engines ranked the highest (see Figure 1). However, based on a box plot analysis (see Figure 2) for three product categories (luxury products, home appliances & electronics, and construction & renovation), the whiskers reach 6, indicating that a fairly large number of consumers regularly use AI applications, especially for these product categories. Extremes (dots and asterisks in Figure 2) are also noted for almost all categories.

Figure 2. Box plot of AI applications and use frequency for product categories.

Note: The line inside the box is the median, the bottom of the box 25th percentile (Q1), the top of the box 75th percentile (Q3), the upper whisker extends to the highest value ≤ (Q3 + 1.5 × (Q3-Q1)), Dots (°) are mild outliers, Asterisks (*) are extreme outliers.

Conclusions and future research

We can conclude that there are clear differences in the extent to which different information sources are used by consumers for different types of products. Unsurprisingly, groceries rank lowest overall, which can be explained at least in part by the habitual and routine nature of grocery shopping (i.e., low involvement) and plausibly high existing knowledge of the products. High-involvement products such as luxury products again ranked the highest.

AI applications and online chat services were not widely used as information sources in most product categories, although there were indicators of fairly frequent use in three product categories (luxury, household appliances and electronics, and construction and renovation) and in all other categories heavy users (extremes) were also identified. This suggests that AI is more commonly used to search for information within product categories that are typically classified as high-involvement products. These types of products are often rarely purchased, and therefore low existing knowledge or experience of the products can be a main trigger for the use of AI applications. On the other hand, heavy AI users were found in all categories, which may suggest other precursors to AI use as well. There are also various question marks regarding the AI-generated information, such as how reliable and objective it is in different situations (Kim & Priluck, 2025). A major and ongoing challenge with AI in retail is the potential for bias (Gielens, 2024). Thus, consumer trust in AI applications can also explain their use (non-use). Uncertainty is a major theme in consumer information search in general (Haridasan et al., 2021). The following research question could be asked in future research: What are the determining factors for why AI information retrieval is more common in some product categories than in others?

Overall, we can conclude that AI applications have not yet emerged as a primary source of information when Finnish consumers shop for goods, but the precursors to their use in different product categories are an interesting avenue for further research. It should also be noted that AI applications are only emerging as an integral part of, for example, search engines, which were ranked as the most used information source. AI applications as an integral part of other information sources are therefore a likely future scenario that can help consumers with faster and more accurate searches before buying goods.

The Finnish Retail Research Foundation conducts the survey annually among Finnish consumers, and we intend to follow up on these results in the future. The analysed survey from 2024 was the first to include AI applications as an information source for product search.

Niklas Eriksson, Principal Lecturer in Digital Marketing, Arcada

Joel Mero, Associate Professor of Marketing, University of Jyväskylä

References

Akalamkam, K. & Mitra, J. K. (2017). Consumer Pre-purchase Search in Online Shopping: Role of Offline and Online Information Sources, Business Perspectives and Research, 6(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533717730448

Beharrell, B. and Denison, T. J. (1995). Involvement in a routine food shopping context. British Food Journal, 97(4), 24-29. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709510085648

Bettman, J. R., Johnson, E. J. & Payne, J. W. (1991). Consumer decision making. I: Handbook of Consumer Behavior, Robertson, T. S and Kassarjian, H. H. (red.), Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Broilo, P. L., Espartel, L. B. & Basso, K. (2016). Pre-purchase information search: too many sources to choose, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 10(3), 193-21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-07-2015-0048

Data: Finnish Retail Research Foundation (2024). Purchasing survey 2024. Distributed by J. Mero, University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

Eriksson, N., Rosenbröijer, C.-J., & Fagerstrøm, A. (2018). Smartphones as decision support in retail stores – The role of product category and gender. Procedia Computer Science, 138, 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.070

Gielens, K. (2024). Making AI work in retail: The vital role of human interaction. Journal of Retailing, 100(2), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2024.05.006

Haridasan, a. C., Fernando, A. G. & Saju B. (2021). A systematic review of consumer information search in online and offline environments. RAUSP Management Journal, 56(2), 234–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-08-2019-0174

Kim, S. & Priluck, R. (2025). Consumer Responses to Generative AI Chatbots Versus Search Engines for Product Evaluation. Journal of Theoretical and Applied. Electronic Commerce Research, 20, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020093

Pham, V. K., Pham Thi, T. D., & Duong, N. T. (2024). A Study on Information Search Behavior Using AI-Powered Engines: Evidence From Chatbots on Online Shopping Platforms. SAGE Open, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244024130000

Santos, S., & Gonçalves, H. M. (2024). Consumer decision journey: Mapping with real-time longitudinal online and offline touchpoint data. European Management Journal, 42(3), 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2022.10.001

Singh, S. & Swait, J. (2017). Channels for search and purchase: Does mobile Internet matter?, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 39, 123-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.05.014

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the Involvement Construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341-352. https://www.jstor.org/stable/254378